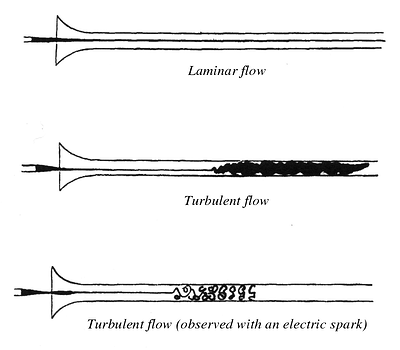

Fluid flows can be divided into two different types: laminar flows and turbulent flows. Laminar flow occurs when the fluid flows in infinitesimal parallel layers with no disruption between them. In laminar flows, fluid layers slide in parallel, with no eddies, swirls or currents normal to the flow itself. This type of flow is also referred as streamline flow because it is characterized by non-crossing streamlines (figure 1).

The laminar regime is ruled by momentum diffusion, while the momentum convection is less important. In more physical terms, it means that viscous forces are higher than inertial forces.

Figure 1: (a) Laminar flow in a closed pipe, (b) Turbulent flow in a closed pipe

History

The distinction between laminar and turbulent regimes was first studied and theorized by Osborne Reynolds in the second half of the 19th century. His first publication on this topic is considered a milestone in the study of fluid dynamics and can be accessed at:

«An experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 35 (224-226): 84–99. 1883»^1

This work was based on the experiment used by Reynolds to show the transition from the laminar to the turbulent regime.

The experiment consisted of examining the behavior of a water flow in a large glass pipe; in order to visualize the flow, Reynolds injected a small vein of dyed water into the flow and observed its behavior at different flow rates. When the velocity was low, the dyed layer remained distinct through the entire length of the pipe. When the velocity was increased, the vein broke up and diffused throughout the tube’s cross-section, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Reynold’s experimental observation of the transition phase.

Thus, Reynolds demonstrated the existence of two different flow regimes, called laminar flow and turbulent flow, separated by a transition phase. He also identified a number of factors which affect the occurrence of this transition.

Reynolds Number

The Reynolds number (Re) is an adimensional number expressing the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. The concept was first introduced by George Gabriel Stokes in 1851 but was popularized by Osborne Reynolds, who proposed it as the parameter used to identify the transition between laminar and turbulent flows. For this reason, the dimensionless number was named by Arnold Sommerfeld after Osborne Reynolds in 1908 ^2.

The Reynolds number is a macroscopic parameter of a flow in its globality and is mathematically defined as:

where:

- \rho is the density of the fluid

- u is the macroscopic velocity of the fluid

- d is the characteristic length of the involved phenomenon

- \mu is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid

- \nu is the cinematic viscosity of the fluid

At low values of Re, the flow is laminar. When Re exceeds a certain threshold, a non-fully developed turbulence occurs in the flow; this regime is usually referred as “transition regime” and occurs for a certain range of the Reynolds number. Finally, over a certain value of Re, the flow becomes fully turbulent; the mean value of Re in the transition regime is usually named “critical Reynolds number” and it is considered the threshold between the laminar and the turbulent flow.

It is interesting to notice that the Reynolds number depends both on the material properties of the fluid and on the geometrical properties of the application. This has two main consequences in the use of this number:

- the Reynolds number is meant to describe the global behavior of a flow, not its local behavior; in large domains, it is possible to have small/localized turbulent regions which do not extend to the whole domain. For this reason, it is very important to understand the physics of the flow to determine the good domain of application and the good characteristic length.

- the Reynolds number is a property of the application. Different applications or different configurations of the same application may have different critical Reynolds numbers.

Transition regime

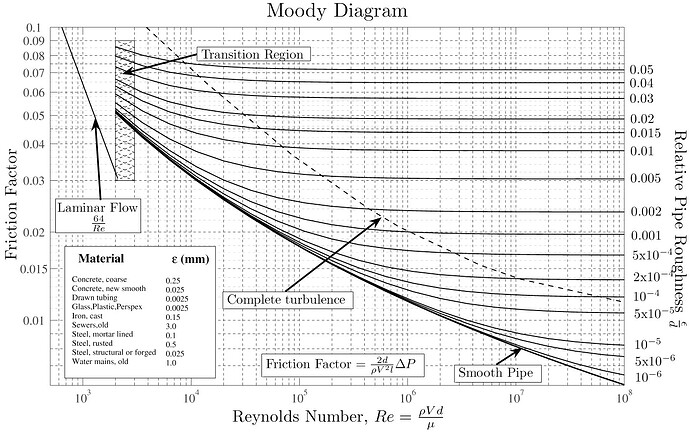

The transition regime is a regime which separates the laminar and the turbulent flows. It occurs for a range of Reynolds number in which laminar and turbulent regimes cohabit in the same flow; this happens because the Reynolds number is a global estimator of the turbulence and does not characterize the flow locally. In fact, other parameters may affect the flow regime locally. An example is the flow in a closed pipe, studied analytically through the Moody’s chart (figure 3), in which the behavior of the flow (described through the friction factor) depends both on the Reynolds number and the relative roughness [3]. The relative roughness is a “local” factor, which indicates the presence of a region that behaves differently because of its proximity to the boundary. Fully turbulent flows are reported on the right of the chart (where the curve is flat) and occur for high Re and/or high values of roughness, which perturbs the flow. On the left, the laminar regime is described and it is linear and independent of the roughness. The most interesting part is the central one, the transition regime, in which the friction factor is highly dependent on both the Reynolds number and the relative roughness. Also, the description of the beginning of the turbulent regime is not reliable, because of its aleatory nature.

Figure 3: Moody Diagram

Application

Laminar flows have both academic and industrial applications.

Many flows in the laminar regime are used as benchmarks for the development of advanced simulation techniques. This is the case of the “lid-driven cavity” ^4, described in figure 4(a), which shows a critical Reynolds number of Re=1000. The resulting velocity field (figure 4(b)) depends on the Reynolds number and the main flow characteristics (e.g. number of eddies, eddies center’s position, velocity profile) have been extensively benchmarked.

Figure 4: Lid-driven cavity: (a) Geometry and boundary conditions; (b) Streamlines for Re=500

From the industrial point of view, the laminar regime is usually developed in flows with low velocity, low density or high viscosity.

This is usually the case of natural convection (figure 5(a)) or ventilation systems working at low velocity (figure 5(b)).

Figure 5(a): Natural convection inside a light bulb; 5(b): Ventilation system inside a cleanroom

Related Issues

To be implemented

Resources

^1: “An experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 35 (224-226): 84–99

^2:” Arnold Sommerfeld: Science, Life and Turbulent Times 1868-1951”, Michael Eckert. Springer Science & Business Media, 24 giu 2013.

^3: Moody, L. F. (1944), “Friction factors for pipe flow”, Transactions of the ASME, 66 (8): 671–684

^4: C.T. Shin U. Ghia, K.N. Ghia. High-Resolution for incompressible flow using the Navier-Stokes equations and the multigrid method. J. Comput. Phys., 48:387–411, 1982.